Web Application Security

By Himanshu Shekhar , 09 Jan 2022

Module 01 : OS Command Injection

This module explains OS Command Injection, a critical vulnerability where attackers execute operating system commands through a vulnerable application. Understanding this vulnerability is essential for web security, penetration testing, and secure software development.

1.1 What is OS Command Injection?

OS Command Injection happens when an application passes user-controlled input directly to the operating system without proper validation.

User input → OS command → system executes it blindly.

1.2 How OS Command Injection Works

- User submits crafted input

- Application builds a system command

- Input is not sanitized

- OS executes attacker-controlled commands

1.3 Common Attack Vectors

- File name parameters

- Ping or traceroute features

- System utilities exposed via web apps

- Admin panels and diagnostic tools

1.4 Impact & Real-World Examples

- Full server compromise

- Data theft

- Malware installation

- Privilege escalation

1.5 Prevention & Secure Coding Practices

- Avoid system command execution when possible

- Use safe APIs instead of shell commands

- Validate and whitelist input

- Apply least privilege

- Log and monitor command execution

Module 02-A : How Domains & DNS Work (Complete Flow)

This module explains how domains and DNS work step by step, from the moment a user types a domain name into a laptop browser to the moment the website loads. Understanding this flow is mandatory for penetration testers, because every web attack starts with DNS and domain resolution. This module is aligned with CEH, OWASP, and real-world reconnaissance techniques.

2A.1 What is a Domain Name?

Definition

A domain name is a human-readable identifier used to locate a resource on the internet. While users interact with domain names, computers and networks communicate using IP addresses. The domain name acts as a logical reference that is translated into an IP address through the Domain Name System (DNS).

Technically, a domain name is not a server or an application. It is a naming and addressing mechanism that helps systems discover where a service is hosted.

Humans remember names. Computers route traffic using numbers. Domain names connect the two.

Why Domain Names Exist

- IP addresses are difficult to remember and manage

- Servers can change IPs without affecting users

- Domains provide identity, branding, and trust

- They allow organizations to scale infrastructure easily

Structure of a Domain Name

Domain names follow a hierarchical structure and are read from right to left. Each level represents an administrative boundary.

Example domain:

www.stardigitalsoftware.com

- .com → Top-Level Domain (TLD)

- stardigitalsoftware → Second-Level Domain (registered name)

- www → Subdomain / service label

Top-Level Domains (TLDs)

A Top-Level Domain (TLD) is the highest level in the domain hierarchy. It defines the general purpose, category, or geographic region of a domain.

Common Generic TLDs (gTLDs)

- .com – Commercial organizations (most widely used)

- .org – Non-profit and community organizations

- .net – Network services and infrastructure

- .info – Informational websites

- .edu – Educational institutions (restricted)

Country Code TLDs (ccTLDs)

- .in – India

- .us – United States

- .uk – United Kingdom

🏢 Real-World Example: StarDigitalSoftware.com

Consider the domain stardigitalsoftware.com.

Its structure and usage in a professional environment might look like this:

stardigitalsoftware.com– Main company websitewww.stardigitalsoftware.com– Public-facing web applicationapi.stardigitalsoftware.com– Backend API serviceslogin.stardigitalsoftware.com– Authentication serviceadmin.stardigitalsoftware.com– Internal admin panel

🔐 Domain Names from a Security & Pentesting Perspective

For security professionals and penetration testers, a domain name is the starting point of reconnaissance. A single domain can reveal:

- Hidden or forgotten subdomains

- Exposed development or staging environments

- Email and authentication infrastructure

- Misconfigured DNS records

A domain name is not just an address — it is a blueprint of an organization’s internet-facing infrastructure.

Understanding domain names and TLDs is fundamental for web architecture, DNS resolution, and effective penetration testing.

What are Subdomains?

A subdomain is a child domain that exists under a main (registered) domain. Subdomains are commonly used to separate services, applications, environments, or business functions within the same organization.

Technically, subdomains are labels added to the left side of a registered domain and are fully controlled through DNS records.

A subdomain is like a separate door to a different service inside the same building.

🧱 Subdomain Structure Explained

Consider the domain:

login.api.stardigitalsoftware.com

- .com → Top-Level Domain (TLD)

- stardigitalsoftware → Registered domain

- api → Subdomain (service layer)

- login → Sub-subdomain (specific function)

🏢 Common Real-World Subdomain Usage

www.example.com– Main websiteapi.example.com– Backend APIsauth.example.com– Authentication servicesadmin.example.com– Administrative interfacemail.example.com– Email servicesdev.example.com– Development environmenttest.example.com– Testing or staging environment

🌍 Subdomains in Enterprise Environments

Large organizations rely heavily on subdomains to manage different environments and business units.

- Production:

app.company.com - Staging:

staging.app.company.com - Development:

dev.app.company.com - Internal tools:

intranet.company.com

2A.2 Domain vs IP Address

🌐 Why IP Addresses Exist

Every device connected to the internet is assigned an IP address (Internet Protocol address). IP addresses act as unique numerical identifiers that allow computers, servers, and network devices to locate and communicate with each other across networks.

Unlike humans, computers cannot interpret names. Network communication is fundamentally based on numeric addressing and routing, which is why IP addresses are mandatory for all internet traffic.

🧠 What an IP Address Represents

- A unique identifier for a device on a network

- A routing destination used by routers and switches

- A logical location, not a physical one

- A requirement for any TCP/IP communication

Without IP addresses, the internet cannot route packets.

📊 Domain vs IP Address (Conceptual Comparison)

- Domain Name: A human-friendly alias (e.g.,

google.com) - IP Address: A machine-friendly identifier (e.g.,

142.250.190.14)

A domain name does not replace an IP address. It simply provides a readable layer on top of it. Before any connection is established, the domain must be translated into an IP address using DNS.

🔄 Static vs Dynamic IP Addresses

- Static IP: Fixed address, commonly used by servers

- Dynamic IP: Changes periodically, commonly used by clients

Domains allow services to remain accessible even if the underlying IP address changes. This abstraction is critical for cloud, load-balanced, and distributed systems.

🌍 IPv4 vs IPv6

- IPv4: 32-bit addressing (e.g.,

192.168.1.1) - IPv6: 128-bit addressing (e.g.,

2001:db8::1)

🏢 Real-World Example (Enterprise Perspective)

Consider a company website hosted in the cloud:

www.company.com→ Load balancer- Load balancer → Multiple backend servers

- Each backend server has its own private IP

The user never sees these IP changes because the domain remains constant.

🔐 Security & Pentesting Perspective

From a security standpoint, understanding the relationship between domains and IP addresses is critical.

- Multiple domains may resolve to the same IP

- One domain may resolve to multiple IPs (round-robin DNS)

- IP-based restrictions can often be bypassed using domains

- Direct IP access may expose services hidden behind domains

🧠 Professional Insight

For penetration testers, resolving domains to IPs helps identify:

- Shared hosting environments

- Cloud providers and infrastructure

- Hidden or legacy services

- Attack surface beyond the main website

Domains are for usability and branding; IP addresses are for routing and communication. Security professionals must understand both.

2A.3 What is DNS & Why It Exists

📖 Definition

The Domain Name System (DNS) is a globally distributed, hierarchical naming system that translates human-readable domain names into machine-readable IP addresses. DNS acts as a critical control plane of the internet, enabling users to access services without knowing their underlying network locations.

From a technical standpoint, DNS is not a single server or database. It is a federated system made up of millions of servers, each responsible for a specific portion of the namespace.

DNS tells your computer where a domain lives on the internet.

🧠 Why DNS is Required

- Humans cannot easily remember numerical IP addresses

- IP addresses may change, but domain names remain stable

- Large-scale services require flexible and dynamic routing

- DNS enables global scalability and decentralization

🌐 DNS as an Abstraction Layer

DNS provides a layer of abstraction between users and infrastructure. Organizations can move servers, change cloud providers, add load balancers, or deploy new regions without changing the domain name users rely on.

This abstraction is foundational to modern technologies such as:

- Cloud computing and elastic infrastructure

- Content Delivery Networks (CDNs)

- High availability and failover architectures

- Microservices and API-based systems

🗂️ Distributed & Hierarchical Design

DNS is designed to be both distributed and hierarchical, ensuring resilience and performance. No single DNS server contains all domain information.

- Root servers know where TLD servers are

- TLD servers know authoritative servers for domains

- Authoritative servers store actual DNS records

🔄 Why DNS Is Faster Than It Looks

Although DNS resolution involves multiple steps, it is optimized through aggressive caching. Responses are cached at multiple layers to reduce latency.

- Browser-level DNS cache

- Operating system DNS cache

- ISP or resolver cache

- Enterprise DNS infrastructure

🏢 DNS in Real-World Enterprise Environments

In enterprise and cloud environments, DNS is not just a name resolution tool — it is a traffic management system.

- Routing users to the nearest data center

- Failover during outages

- Separating internal and external services

- Service discovery in microservices architectures

🔐 DNS from a Security Perspective

DNS is also a critical security component. Because all web traffic depends on DNS, attackers freq

2A.4 DNS Resolution Process (Recursive vs Iterative)

📖 What is DNS Resolution?

DNS resolution is the technical process of converting a domain name into its corresponding IP address. This process determines who asks whom, in what order, and how trust is delegated across the DNS hierarchy.

DNS resolution is not a single request — it is a controlled conversation between multiple servers.

🧠 Two Fundamental Resolution Models

DNS resolution operates using two distinct models:

- Recursive Resolution

- Iterative Resolution

🔁 Recursive DNS Resolution

In recursive resolution, the client asks a DNS server to resolve the domain completely. The server takes full responsibility for finding the final answer.

- The client sends one request

- The resolver performs all lookups on behalf of the client

- The client never talks to root or TLD servers directly

Example:

Browser → Recursive Resolver → Final IP🔄 Iterative DNS Resolution

In iterative resolution, each DNS server responds with the best information it has, usually a referral to another server.

- Root servers respond with TLD server addresses

- TLD servers respond with authoritative server addresses

- No server performs the full lookup alone

🧭 Combined Real-World Flow

In reality, DNS uses both models together:

- Client makes a recursive query to resolver

- Resolver performs iterative queries to DNS hierarchy

- Resolver returns the final answer to the client

🏢 Why This Design Exists

- Reduces complexity for clients

- Improves performance via caching

- Protects root and TLD servers from direct user traffic

- Centralizes policy and security controls

🔐 Security & Pentesting Perspective

- Open recursive resolvers can be abused

- Weak recursion controls enable cache poisoning

- Understanding flow helps locate trust boundaries

Root DNS Servers → point to TLD servers (.com, .org, .net, .in)

TLD DNS Servers → point to Authoritative DNS servers

Authoritative DNS → returns the final IP address

User / Browser

↓

Browser DNS Cache

↓

Operating System DNS Cache

↓

HOSTS File

↓

Recursive DNS Resolver (ISP / 8.8.8.8 / 1.1.1.1)

↓

Root DNS Servers → point to TLD servers (.com, .org, .net, .in)

↓

TLD DNS Servers → point to Authoritative DNS servers

↓

Authoritative DNS → returns the final IP address

↓

Recursive Resolver (caches response)

↓

Browser connects to the IP (TCP → HTTPS)

Attackers don’t attack DNS everywhere — they attack the recursive resolver.

DNS resolution is a layered process combining recursive convenience with iterative delegation.

2A.5 DNS Query Types (Recursive, Iterative, Non-Recursive)

📖 What is a DNS Query?

A DNS query is a request for information sent to a DNS server. Query types define how much work the server must do and how responsibility is shared.

🔁 1. Recursive Query

A recursive query requires the DNS server to return a final answer or an error.

- Client demands a complete resolution

- Server cannot reply with referrals

- Most common query type used by users

Example:

Client → Resolver: “Give me the IP for example.com”🔄 2. Iterative Query

In an iterative query, the DNS server replies with the best information it has, usually a referral.

- Server does not resolve fully

- Client continues querying other servers

- Used between DNS infrastructure components

Example:

Resolver → Root → TLD → Authoritative📦 3. Non-Recursive Query

A non-recursive query is answered directly from a server’s local data or cache.

- No additional lookups are performed

- Fastest DNS response type

- Used heavily in caching scenarios

🧭 Query Type Comparison

- Recursive: “You must find the answer”

- Iterative: “Tell me what you know”

- Non-Recursive: “Answer from cache or zone”

🏢 Where Each Query Type is Used

- Browsers → Recursive queries

- Resolvers → Iterative queries

- Authoritative servers → Non-recursive responses

🔐 Security & Pentesting Perspective

- Open recursion = amplification & poisoning risk

- Non-recursive behavior reveals caching behavior

- Query analysis helps identify resolver weaknesses

DNS query types define responsibility, performance, and security boundaries.

2A.6 Types of DNS Servers

🗂️ DNS Server Roles (Big Picture)

DNS works through a hierarchy of specialized server types, each with a clearly defined responsibility. No single DNS server knows all domain-to-IP mappings. Instead, servers cooperate to resolve queries efficiently and reliably.

🌍 1. Root DNS Servers

Root DNS servers sit at the top of the DNS hierarchy. They do not store IP addresses for domains. Instead, they direct queries to the appropriate Top-Level Domain (TLD) servers.

- They know where

.com,.org,.net, etc. are managed - They respond with referrals, not final answers

- There are 13 logical root server clusters (A–M)

🧭 2. TLD (Top-Level Domain) DNS Servers

TLD DNS servers manage domains under a specific

top-level domain such as .com, .org,

or country-code domains like .in.

- They know which authoritative servers are responsible for a domain

- They do not store IP addresses for individual hosts

- They act as a directory for domain ownership

Example:

A TLD server for .com knows where

stardigitalsoftware.com is managed,

but not its actual IP address.

📍 3. Authoritative DNS Servers

Authoritative DNS servers provide the final, trusted answers to DNS queries. They store the actual DNS records configured for a domain.

- Store records like A, AAAA, CNAME, MX, TXT

- Controlled by the domain owner or hosting provider

- Define how services are accessed

🔁 4. Recursive DNS Resolvers

Recursive resolvers act on behalf of users. They perform the full DNS lookup process by querying root, TLD, and authoritative servers.

- Used by browsers, operating systems, and networks

- Cache responses to improve performance

- Examples: ISP resolvers, Google DNS, Cloudflare DNS

🏢 5. Forwarding & Internal DNS Servers

In enterprise environments, organizations often deploy internal DNS servers that forward requests to upstream resolvers.

- Resolve internal hostnames

- Enforce security policies

- Log DNS activity for monitoring

🔄 How These Servers Work Together (High-Level Flow)

- Client sends query to a recursive resolver

- Resolver queries a root server

- Root server refers to a TLD server

- TLD server refers to an authoritative server

- Authoritative server returns the final answer

- Resolver caches and returns the response to the client

🔐 Security & Pentesting Perspective

Understanding DNS server roles helps security professionals identify attack vectors and misconfigurations.

- Open recursion vulnerabilities

- Zone transfer misconfigurations

- Cache poisoning risks

- Weak DNS access controls

DNS attacks often succeed because administrators misunderstand server roles and trust boundaries.

DNS is a cooperative system where each server type performs a specific task. Security and reliability depend on correct role separation.

2A.7 DNS Records Explained

DNS records are structured instructions stored on authoritative DNS servers. They define how a domain behaves, where services are hosted, and how external systems should interact with the domain.

From an enterprise and security perspective, DNS records are extremely valuable because they often reveal infrastructure details, third-party services, and security controls.

📍 A Record (Address Record)

An A record maps a domain or subdomain directly to an IPv4 address. This is the most common DNS record type.

- Used for websites, APIs, and backend services

- Can point to a single server or a load balancer

- Multiple A records enable basic load balancing

www.example.com → 203.0.113.10

📍 AAAA Record (IPv6 Address Record)

An AAAA record performs the same function as an A record but maps a domain to an IPv6 address.

- Required for IPv6-only networks

- Often deployed alongside A records

- Increasingly important for modern infrastructure

api.example.com → 2001:db8::1

🔁 CNAME Record (Canonical Name)

A CNAME record creates an alias that points one domain name to another domain name instead of an IP address.

- Commonly used with cloud services and CDNs

- Allows infrastructure changes without DNS updates

- Cannot coexist with other record types at the same name

cdn.example.com → example.cdnprovider.net

📧 MX Record (Mail Exchange)

An MX record defines which mail servers are responsible for receiving email for a domain.

- Uses priority values (lower = higher priority)

- Often points to third-party email providers

- Critical for email reliability and security

example.com → mail.example.com (priority 10)

📝 TXT Record (Text Record)

A TXT record stores arbitrary text data associated with a domain. While originally generic, TXT records are now heavily used for security and verification.

- Domain ownership verification

- Email security (SPF, DKIM, DMARC)

- Cloud service validation

v=spf1 include:_spf.google.com ~all

🔐 Security-Relevant DNS Records

Some DNS records directly impact security posture and are frequently reviewed during penetration tests.

- SPF – Controls which servers can send email

- DKIM – Cryptographically signs emails

- DMARC – Defines email authentication policy

- CAA – Restricts certificate authorities

🏢 DNS Records in Enterprise Environments

In enterprise and cloud architectures, DNS records are used as a control layer for routing, security, and service discovery.

- Traffic steering across regions

- Failover during outages

- Integration with third-party SaaS platforms

- Zero-downtime migrations

🔍 DNS Records from a Pentester’s Perspective

DNS records often leak valuable reconnaissance data:

- Cloud providers and CDNs

- Email infrastructure

- Third-party integrations

- Forgotten or deprecated services

DNS records are not just configuration data — they define service behavior, trust relationships, and security boundaries.

2A.8 Step-by-Step: What Happens When You Search a Domain

🔄 High-Level Overview

When a user enters a domain name into a browser, a series of network, DNS, and protocol-level operations take place before any web page is displayed. This process is optimized through caching and retries, making subsequent visits significantly faster.

DNS resolution always happens before HTTP or HTTPS communication.

🧭 First-Time Visit: Complete DNS Resolution Flow

The following steps describe what happens when a domain is accessed for the first time (no cached DNS entries exist).

-

User enters a domain in the browser

Example:www.example.com

The browser parses the input, identifies it as a Fully Qualified Domain Name (FQDN), and determines that name resolution is required before any network connection can be made.

⚠️ At this point, the browser has no idea where the website is hosted. -

Browser DNS cache is checked

Modern browsers maintain their own DNS cache to reduce latency and repeated lookups. This cache is isolated per browser and usually has a very short lifetime.

✔️ If a valid entry exists here, the entire DNS resolution process is skipped. -

Operating System DNS cache is checked

The operating system maintains a system-wide DNS cache shared by all applications. This cache is populated by previous resolutions and responses from DNS resolvers.

💡 Commands likeipconfig /displaydnsorsystemd-resolve --statisticsexpose this layer. -

Hosts file is checked

The OS checks the localhostsfile for manually defined domain-to-IP mappings. This file has higher priority than DNS.

🚨 From a security perspective, malware frequently abuses this file to silently redirect traffic. -

DNS query sent to Recursive Resolver

If no local mapping exists, the OS sends a recursive DNS query to the configured resolver (ISP DNS, enterprise DNS, or public resolvers like Google8.8.8.8or Cloudflare1.1.1.1).

The client essentially says:

“I don’t care how — give me the final IP address.” -

Resolver checks its own cache

The recursive resolver maintains a large shared cache used by thousands or millions of clients. If the record exists and TTL has not expired, the resolver responds immediately.

✔️ This step is why DNS appears fast for most users. -

Resolver queries a Root DNS server

If no cache entry exists, the resolver begins iterative resolution. It contacts one of the 13 logical Root DNS servers.

Root servers do not know the IP address. They only reply with:

“Ask the appropriate TLD server.” -

Resolver queries the TLD DNS server

The resolver queries the Top-Level Domain (TLD) server (e.g.,.com,.org,.in).

The TLD server responds with the location of the authoritative DNS servers for the domain.

💡 This step enforces domain ownership boundaries. -

Resolver queries the Authoritative DNS server

The authoritative server is the final source of truth. It returns the actual DNS record:- A record → IPv4 address

- AAAA record → IPv6 address

- CNAME → Alias resolution

-

Resolver caches the response

The resolver stores the DNS response based on its TTL (Time To Live). This cached entry will serve future users until the TTL expires.

⚠️ Incorrect TTL values can cause outages or slow recovery. -

IP address returned to the client

The resolver sends the final IP address back to the operating system, which passes it to the browser.

✔️ DNS resolution is now complete. -

Browser initiates TCP connection

Only after DNS resolution:- TCP three-way handshake begins

- HTTPS negotiation (TLS handshake) occurs

- HTTP requests are finally sent

⚡ Second-Time Visit: Cached Resolution Flow

On subsequent visits, most DNS steps are skipped due to caching. This is why websites load faster the second time.

-

Browser DNS cache is checked

Modern browsers store recently resolved domain names in a short-lived internal cache. If the DNS record exists and the TTL is still valid, the browser immediately retrieves the IP address.

✔️ This is the fastest possible DNS resolution path. -

Operating System DNS cache is checked

If the browser cache does not contain the entry, the operating system’s system-wide DNS cache is queried. This cache is shared by all applications on the system and persists across browser restarts.

💡 This layer is commonly inspected or flushed during troubleshooting. -

Cached response validated against TTL

Before using any cached entry, the system verifies that the TTL (Time To Live) has not expired. If the TTL is still valid, the cached IP is trusted and no external DNS communication is required.

⚠️ Once TTL expires, the cache entry becomes invalid and full DNS resolution is triggered again. -

No external DNS query is required

Because the IP address is already known, the system does not contact:- Recursive DNS resolvers

- Root DNS servers

- TLD DNS servers

- Authoritative DNS servers

-

Browser connects directly to the IP address

With DNS resolution complete from cache, the browser immediately initiates the TCP connection to the server. If HTTPS is used, the TLS handshake follows.

🚀 Page rendering begins almost instantly.

⏱️ DNS TTL (Time To Live)

Every DNS record includes a TTL value that determines how long it can be cached.

- Short TTL → Faster changes, more DNS traffic

- Long TTL → Better performance, slower updates

- Common TTL values: 60s, 300s, 3600s

🔁 What Happens If Something Fails?

DNS resolution includes retries and fallback mechanisms.

- Resolver tries alternative DNS servers

- IPv6 resolution may fall back to IPv4

- Cached stale responses may be used temporarily

- Timeouts trigger retry logic

🔐 Security & Pentesting Perspective

Understanding the full DNS resolution flow allows security professionals to:

- Identify cache poisoning opportunities

- Detect malicious resolvers

- Bypass DNS-based security controls

- Understand redirection attacks

Root DNS Servers → point to TLD servers (.com, .org, .net, .in)

TLD DNS Servers → point to Authoritative DNS servers

Authoritative DNS → returns the final IP address

User / Browser

↓

Browser DNS Cache

↓

Operating System DNS Cache

↓

HOSTS File

↓

Recursive DNS Resolver (ISP / 8.8.8.8 / 1.1.1.1)

↓

Root DNS Servers → point to TLD servers (.com, .org, .net, .in)

↓

TLD DNS Servers → point to Authoritative DNS servers

↓

Authoritative DNS → returns the final IP address

↓

Recursive Resolver (caches response)

↓

Browser connects to the IP (TCP → HTTPS)

DNS attacks succeed not by breaking servers, but by manipulating trust in the resolution process.

DNS resolution is a multi-layered, cached, and resilient process. Understanding each step is essential for performance tuning, troubleshooting, and security testing.

2A.9 DNS Caching

📖 What is DNS Caching?

DNS caching is the process of temporarily storing DNS query results so that future requests for the same domain can be answered faster without repeating the full DNS resolution process.

Caching is a core performance optimization that allows the internet to scale. Without DNS caching, every website visit would require multiple DNS queries to root, TLD, and authoritative servers.

DNS caching remembers answers so the internet doesn’t have to keep asking the same questions.

🧠 Why DNS Caching Exists

- Reduces DNS lookup latency

- Decreases network traffic

- Reduces load on DNS infrastructure

- Improves user experience and page load time

🗂️ Levels of DNS Caching

DNS caching occurs at multiple layers. Each layer may store the same DNS response independently.

1️⃣ Browser DNS Cache

- Maintained by the web browser itself

- Shortest cache lifetime

- Cleared when the browser is restarted (in most cases)

2️⃣ Operating System DNS Cache

- System-wide cache shared by all applications

- Survives browser restarts

- Can be flushed manually (e.g.,

ipconfig /flushdns)

3️⃣ Recursive Resolver / ISP Cache

- Used by ISPs, enterprises, and public DNS providers

- Shared across many users

- Has the greatest performance impact

⏱️ DNS TTL (Time To Live)

Every DNS record includes a TTL value, which defines how long the record may be cached. Once the TTL expires, the record must be refreshed from the authoritative server.

- Short TTL → Faster updates, higher DNS traffic

- Long TTL → Better performance, slower changes

- Typical TTL values: 60s, 300s, 3600s

🔄 Positive vs Negative Caching

DNS caching applies to both successful and failed queries.

- Positive caching: Stores valid DNS answers

- Negative caching: Stores “domain not found” responses

🏢 DNS Caching in Enterprise & Cloud Environments

Enterprises use DNS caching strategically to improve reliability and performance.

- Internal resolvers cache internal service names

- Split-horizon DNS (internal vs external resolution)

- Local caching improves application response time

- Centralized logging of DNS queries

🔐 Security Risks of DNS Caching

While DNS caching improves performance, it also introduces security risks when trust is abused.

- DNS cache poisoning

- Redirection to malicious servers

- Persistence of malicious responses

- Difficulty detecting poisoned caches

🧪 DNS Caching from a Pentester’s Perspective

Security testers analyze DNS caching behavior to:

- Identify weak resolvers

- Test cache poisoning protections

- Understand DNS-based access controls

- Bypass security mechanisms relying on DNS

DNS caching is a performance feature built on trust. Attackers aim to exploit that trust.

DNS caching makes the internet fast and scalable, but improper configuration or weak resolvers can turn it into a powerful attack vector.

2A.10 Where DNS Can Be Attacked

Because DNS is the first dependency of almost all internet communication, it is a highly attractive target for attackers. If an attacker can influence DNS resolution, they can redirect users without touching the web application itself.

🧨 1. DNS Spoofing (DNS Hijacking)

DNS spoofing occurs when an attacker provides false DNS responses, causing a domain to resolve to a malicious IP address. This can happen at multiple points in the resolution chain.

- User is redirected to a fake website

- Credentials are harvested

- Malware may be silently delivered

☠️ 2. DNS Cache Poisoning

DNS cache poisoning targets recursive DNS resolvers. Attackers inject malicious DNS records into the resolver’s cache, causing it to return incorrect IP addresses to many users.

- Affects all users relying on the poisoned resolver

- Persists until TTL expires or cache is flushed

- Often combined with race conditions or weak randomization

🕵️ 3. Malicious or Compromised DNS Resolvers

Not all DNS resolvers are trustworthy. Attackers may operate or compromise resolvers to manipulate DNS responses.

- Public or rogue DNS servers return altered responses

- ISP DNS infrastructure may be compromised

- Enterprise internal resolvers may be misconfigured

🧬 4. Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) Attacks on DNS

DNS queries are traditionally sent in cleartext. This allows attackers on the same network to intercept and modify DNS responses.

- Common on public Wi-Fi networks

- Attackers inject fake DNS responses

- Users are redirected before HTTPS begins

🔓 5. Unauthorized Zone Transfers

DNS zone transfers are used to replicate DNS data between authoritative servers. If misconfigured, attackers can download the entire DNS zone.

- Reveals internal hostnames

- Exposes infrastructure layout

- Provides a full target list for attackers

🧱 6. Subdomain Takeover via DNS Misconfiguration

Subdomain takeovers occur when DNS records (usually CNAMEs) point to resources that no longer exist. Attackers can claim the unused resource and gain control.

- Common with cloud services and CDNs

- Allows full control of the subdomain

- Often leads to phishing or malware delivery

🧠 DNS Attacks in the Real World

Real-world DNS attacks are often subtle and long-lived:

- Users redirected only occasionally

- Attacks limited to specific regions

- Malicious records hidden behind long TTLs

- Detection delayed due to caching

🔐 Security & Pentesting Perspective

Security professionals evaluate DNS attack surfaces by testing:

- Resolver trust and configuration

- Zone transfer permissions

- Dangling DNS records

- DNSSEC deployment

- Logging and monitoring coverage

DNS attacks rarely exploit software bugs — they exploit misplaced trust and misconfiguration.

DNS is a powerful control layer. Any weakness in DNS can silently undermine authentication, encryption, and user trust.

2A.11 DNS from a Pentester’s Perspective

🎯 Why DNS Matters in Pentesting

- Target discovery starts with DNS

- Subdomains reveal hidden services

- DNS records expose infrastructure

If you understand DNS, you understand the attack entry point.

Module 02 : SQL Injection (SQLi)

This module provides an in-depth understanding of SQL Injection (SQLi), one of the most dangerous and widely exploited web application vulnerabilities. SQL Injection allows attackers to interfere with database queries, leading to data theft, authentication bypass, data manipulation, and complete system compromise. This module is fully aligned with CEH, OWASP, and real-world penetration testing practices.

2.1 What is SQL Injection?

🔍 Definition

SQL Injection occurs when an application inserts untrusted user input directly into an SQL query without proper validation or parameterization. This allows attackers to modify the query’s logic.

If user input changes the meaning of an SQL query → SQL Injection exists.

🗄️ Why Databases Are a Prime Target

- Databases store usernames, passwords, emails, and financial data

- Databases often control application behavior

- One vulnerable query can expose the entire system

2.2 How SQL Injection Works (Attack Flow)

🔄 Step-by-Step Breakdown

- User submits input through a form, URL, cookie, or header

- Application builds an SQL query dynamically

- Input is not sanitized or parameterized

- Database executes attacker-controlled SQL

📌 Common Vulnerable Locations

- Login forms

- Search boxes

- Product filters

- URL parameters (GET requests)

- Cookies and HTTP headers

- API parameters

2.3 Types of SQL Injection

🧩 1. In-Band SQL Injection

The attacker receives data through the same channel used to send the request. This is the most common and easiest form.

- Error-based SQL Injection

- Union-based SQL Injection

🧩 2. Blind SQL Injection

The application does not display database errors or results, but the attacker can infer behavior from responses.

- Boolean-based blind SQLi

- Time-based blind SQLi

🧩 3. Out-of-Band SQL Injection

The database sends data to an external system controlled by the attacker. This occurs when in-band methods are not possible.

2.4 Authentication Bypass via SQL Injection

🔓 How Login Bypass Happens

Many applications build login queries using user input. Attackers manipulate conditions to force authentication success.

📌 Impact of Authentication Bypass

- Unauthorized access to user accounts

- Admin panel compromise

- Privilege escalation

- Complete application takeover

2.5 Impact of SQL Injection

💥 Technical Impact

- Data leakage (usernames, passwords, PII)

- Data modification or deletion

- Database corruption

- Remote code execution (in some DBs)

🏢 Business Impact

- Financial loss

- Legal penalties

- Loss of customer trust

- Brand reputation damage

2.6 SQL Injection in Modern Applications

SQL Injection is not limited to old applications. Modern systems can still be vulnerable due to:

- Improper ORM usage

- Dynamic query building

- Legacy code in modern apps

- API-based SQL queries

- Microservices with shared databases

2.7 Prevention & Secure Coding Practices

🛡️ Core Defenses

- Use prepared statements (parameterized queries)

- Never build SQL queries using string concatenation

- Apply strict input validation

- Use least-privileged database accounts

- Disable detailed database error messages

📋 Defense-in-Depth

- Web application firewalls (WAF)

- Database activity monitoring

- Secure error handling

- Logging and alerting

2.8 Ethical Testing & Defensive Mindset

Ethical hackers test SQL Injection vulnerabilities only within authorized environments and scope.

🧠 Defensive Thinking

- Think like an attacker

- Assume all input is hostile

- Design queries safely from day one

- Test continuously

The best defense against SQL Injection is secure application design.

Module 03 : HTTP, Web Protocol & Transport Layer Abuse

This module provides a deep understanding of HTTP, web protocols, and transport-layer mechanisms that form the foundation of all web applications. Instead of focusing on a single vulnerability, this module explains how attackers abuse HTTP methods, headers, sessions, DNS, and TLS to exploit web applications. Mastering this module is critical for penetration testing, bug bounty hunting, secure development, and defensive monitoring.

3.1 HTTP Protocol Overview (Attack Surface)

What is HTTP?

HTTP (HyperText Transfer Protocol) is a stateless, application-layer communication protocol that defines how clients (browsers, mobile apps, API consumers) exchange data with servers over the internet.

Every interaction on a website — viewing pages, logging in, submitting forms, calling APIs, uploading files, or making payments — is translated into one or more HTTP requests and responses.

Web security is HTTP security.

Client–Server Architecture

- Client: Browser, mobile app, API tool (Postman, curl)

- Server: Web server + backend application logic (Apache, Nginx, IIS, Laravel, Spring, Node)

Client ---> HTTP Request ---> Server

Client <--- HTTP Response <--- Server

The server does not see clicks, buttons, or UI elements — it only sees HTTP requests. Everything else is a browser abstraction.

Stateless Nature of HTTP

HTTP is stateless, meaning each request is independent. The server does not automatically remember previous requests.

- No built-in session memory

- No user identity by default

- No request ordering guarantee

Authentication, sessions, and authorization are all built on top of HTTP — not provided by it.

HTTP Trust Model (Why Attacks Exist)

HTTP follows a simple trust model: the server must trust and parse data sent by the client.

- Methods are client-supplied

- Headers are client-supplied

- Parameters are client-supplied

- Bodies are client-supplied

If the client controls the data, attackers control the data.

Why HTTP Is a Massive Attack Surface

- Requests are human-readable and modifiable

- Tools and browsers allow full request control

- Servers rely on parsing logic

- Security decisions are often HTTP-based

Vulnerabilities rarely exist in encryption itself — they exist in how servers interpret and trust HTTP data.

Inherent Limitations of HTTP

- No built-in authentication

- No built-in authorization

- No replay protection

- No input validation

These protections must be implemented by developers, frameworks, and infrastructure — often incorrectly.

Attacker’s View of HTTP

- Every button = request

- Every request = editable

- Every edit = potential vulnerability

If you can control the request, you can test the application.

HTTP is not insecure by itself — insecurity comes from how applications use it.

3.2 HTTP Request Structure & Parsing

Every HTTP request sent by a browser is broken into multiple components. Each component may be parsed by different systems such as load balancers, WAFs, frameworks, and application code. Understanding this parsing chain is critical for web security testing.

Parts of an HTTP Request

- Request Line – Defines intent

- Headers – Metadata & control information

- Body (optional) – User-supplied data

Most web vulnerabilities exist because different components interpret the same request differently.

Request Line (Critical Control Point)

GET /about HTTP/1.1

- GET → HTTP Method (action)

- /about → Resource path

- HTTP/1.1 → Protocol version

The request line defines what the client wants to do. Many security decisions (routing, permissions, caching) depend on how this line is interpreted.

Request Line Abuse Examples

- Changing method (GET → POST)

- Using unexpected paths (/admin vs /Admin)

- Encoding tricks (%2e%2e/)

- HTTP version confusion

Headers (Context & Authority)

Host: www.example.com

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0

Accept: text/html

Authorization: Bearer token

Content-Type: application/json

X-Forwarded-For: 127.0.0.1

Headers provide additional information about the request. Many applications make trust decisions based on headers.

Common Header Roles

- Host – Determines virtual host routing

- Authorization – Authentication identity

- Content-Type – How body is parsed

- X-Forwarded-For – Client IP (often trusted incorrectly)

Headers are fully controlled by the client. Trusting them without validation leads to bypasses.

Body (User-Controlled Data)

{

"username": "Shekhar",

"password": "12345"

}

The body carries user input and is usually processed by application logic, ORMs, and validation layers. Improper parsing here leads to injections and logic flaws.

Body Parsing Risks

- JSON vs form-data confusion

- Duplicate parameters

- Unexpected data types

- Hidden or extra fields

How HTTP Requests Are Parsed (Real Flow)

Browser

↓

CDN / Load Balancer

↓

WAF / Security Layer

↓

Web Server (Nginx / Apache)

↓

Framework (Laravel / Spring / Express)

↓

Application Code

Each layer may parse the request independently. If any layer disagrees with another, attackers can exploit the difference.

If the WAF blocks based on one interpretation but the app executes based on another, security controls fail.

Real-World Parsing Abuse Scenarios

- WAF blocks parameter A, app uses parameter B

- Duplicate headers parsed differently

- Content-Type mismatch bypassing validation

- Method override via headers or body

Most advanced web vulnerabilities are not about breaking encryption — they are about confusing parsers.

3.3 HTTP Request Methods & Misuse

HTTP request methods (also called verbs) tell the server what action the client wants to perform on a resource. Many critical security decisions depend on the method used.

What Are HTTP Methods?

Each HTTP method has defined semantics: whether it should change server state, whether it can be safely repeated, and how it should be protected.

Common HTTP Methods Overview

| Method | Primary Purpose | Security Expectation | Common Abuse |

|---|---|---|---|

| GET | Retrieve data | No state change | Sensitive actions via URL |

| POST | Create / submit data | State change | Missing CSRF protection |

| PUT | Replace resource | Full overwrite | Unauthorized object updates |

| PATCH | Partial update | Field-level changes | Hidden parameter abuse |

| DELETE | Remove resource | Permanent action | Missing authorization checks |

Method Semantics (Why They Matter)

- Safe methods should not modify data

- Unsafe methods must be protected

- Idempotent methods should behave the same on repeat

- Servers must enforce behavior, not trust the method name

Method-by-Method Security Analysis

GET Method

- Used to retrieve data

- Parameters passed via URL

- Should never change server state

Abuse: Account deletion, logout, or payment via GET

POST Method

- Used to submit or create data

- Supports request body

- Not idempotent

Abuse: CSRF, replay attacks, missing validation

PUT Method

- Replaces entire resource

- Idempotent by definition

- Often misconfigured

Abuse: Overwriting other users’ data

PATCH Method

- Updates specific fields

- Common in modern APIs

- High-risk for logic flaws

Abuse: Modifying restricted fields (role, price)

DELETE Method

- Deletes a resource

- Idempotent but destructive

- Must enforce strict authorization

Abuse: Deleting other users’ resources

Method Override & Confusion Attacks

Some frameworks allow method override using headers or parameters.

POST /user/5

X-HTTP-Method-Override: DELETE

- WAF checks POST, app executes DELETE

- Authorization applied inconsistently

Required Security Controls Per Method

- Authentication – who is the user?

- Authorization – can they perform THIS action?

- CSRF protection – for unsafe methods

- Rate limiting – for destructive operations

Authorization must be enforced per method, per resource, and per user — not just per endpoint.

Most authorization bugs happen because developers protect URLs but forget to protect methods.

3.4 Safe vs Unsafe HTTP Methods

HTTP methods are classified as safe or unsafe based on whether they are intended to change server state. This classification has important security implications, but it is often misunderstood or misused by developers.

🟢 Safe HTTP Methods (By Definition)

Safe methods are designed to not modify server-side data. They are typically used for read-only operations.

- GET – Retrieve a resource

- HEAD – Retrieve headers only

“Safe” means no state change — it does NOT mean secure.

Common Misuse of Safe Methods

- Account logout via GET

- Password reset triggers via GET

- Delete actions using query parameters

- Financial actions via clickable links

If a GET request changes data, it becomes vulnerable to CSRF, caching, prefetching, and link abuse.

Unsafe HTTP Methods

Unsafe methods are intended to modify server state. They require strict security controls.

- POST – Create or submit data

- PUT – Replace a resource

- PATCH – Partially update data

- DELETE – Remove a resource

Required Protections for Unsafe Methods

- Strong authentication

- Per-object authorization checks

- CSRF protection (for browser clients)

- Rate limiting

- Audit logging

Safe vs Unsafe Methods – Security Comparison

| Aspect | Safe Methods | Unsafe Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Server State Change | No (by design) | Yes |

| CSRF Protection Needed | Usually No | Yes |

| Cacheable | Often Yes | No |

| Common Misuse | Hidden state changes | Missing authorization |

Pentester Perspective

- Never trust the method label

- Observe real server behavior

- Test GET requests for side effects

- Test unsafe methods for missing authorization

Hidden endpoints, internal APIs, and “not linked” URLs are still attackable if unsafe methods are exposed.

Safe vs unsafe is a protocol concept. Security depends on implementation, not intent.

3.5 Idempotent Methods & Replay Risks

Idempotency is a core HTTP concept that defines how a request behaves when it is sent multiple times. Misunderstanding idempotency is a major cause of replay attacks and business logic flaws.

What Is Idempotency?

An idempotent request produces the same result no matter how many times it is repeated with the same input.

One request or ten identical requests → same outcome.

Examples

- GET /users/5 → always returns user 5

- PUT /users/5 → user is updated to the same final state

- DELETE /users/5 → user is deleted (once)

Idempotency by HTTP Method

| Method | Idempotent | Why |

|---|---|---|

| GET | Yes | No state change |

| PUT | Yes | Final state is same |

| DELETE | Yes | Resource ends in deleted state |

| POST | No | Each request creates new action |

Idempotent does NOT mean safe. DELETE is idempotent but extremely dangerous.

What Is a Replay Attack?

A replay attack occurs when an attacker captures a valid request and sends it again — one or more times — to repeat the same action.

Original Request ---> Accepted by Server

Replay Request ---> Accepted Again ❌

Common Replay Attack Scenarios

- Repeating a payment request

- Reusing a discount or coupon API

- Replaying OTP verification requests

- Repeating account credit or wallet top-up

- Replaying password reset confirmations

If the server accepts the same request twice, the attacker gets the action twice.

Why Replay Attacks Work

- No request uniqueness enforced

- No nonce or timestamp validation

- Trusting client-side state

- Missing server-side tracking

HTTP itself has no built-in replay protection. Developers must explicitly add it.

📱 Replay Risks in APIs & Mobile Apps

- Mobile apps reuse tokens

- APIs accept identical JSON payloads

- No CSRF protection in APIs

- Attackers can automate replay easily

🛡️ Anti-Replay Protection Techniques

- Unique request IDs (idempotency keys)

- One-time tokens or nonces

- Timestamp + expiry validation

- Server-side request tracking

- Rate limiting critical endpoints

Idempotency-Key: 9f8c7a12-unique-id

🧪 Pentester Testing Checklist

- Capture a valid request

- Send it again without modification

- Send it multiple times rapidly

- Change timing but keep payload same

- Observe balance, state, or response changes

Replay attacks are logic flaws — they often leave no errors or crashes.

If a request can be repeated safely, it should be idempotent. If it cannot be repeated, it must be protected against replay.

3.6 HTTP Response Status Codes & Attack Indicators

HTTP response status codes tell the client how the server interpreted and processed a request. For attackers and pentesters, response codes act like debug signals revealing authentication logic, authorization boundaries, validation behavior, and error handling.

Attackers don’t guess — they observe responses.

1xx – Informational Responses

1xx responses indicate that the request was received and the server is continuing processing. These are rarely seen in browsers but may appear in low-level HTTP tools.

- 100 Continue – Server is ready to receive request body

- 101 Switching Protocols – Protocol upgrade (e.g., WebSocket)

1xx responses are sometimes abused in request smuggling and proxy desynchronization attacks.

2xx – Success Responses

2xx responses indicate that the server accepted and processed the request successfully. However, success does not always mean security.

- 200 OK – Request processed normally

- 201 Created – New resource created

- 202 Accepted – Request accepted but not completed

- 204 No Content – Action succeeded, no response body

Attack Indicators (2xx)

- 200 on unauthorized actions → IDOR

- 200 on admin endpoints → access control failure

- 204 on DELETE without auth → silent data loss

A successful response to an unauthorized request is a critical vulnerability.

3xx – Redirection Responses

3xx responses instruct the client to perform another request. They are commonly used in login flows, workflows, and navigation.

- 301 / 302 – Permanent / Temporary redirect

- 303 See Other – Redirect after POST

- 307 / 308 – Method-preserving redirect

Attack Indicators (3xx)

- Redirect loops → logic flaws

- Redirect after failed auth → bypass attempts

- Open redirects → phishing & token leakage

Unexpected redirects often reveal broken authentication or workflow flaws.

4xx – Client Error Responses

4xx responses indicate that the request was rejected due to client-side issues. These codes reveal validation, auth, and permission logic.

- 400 Bad Request – Malformed input

- 401 Unauthorized – Authentication required

- 403 Forbidden – Authenticated but not allowed

- 404 Not Found – Resource hidden or missing

- 405 Method Not Allowed – Wrong HTTP method

- 429 Too Many Requests – Rate limiting triggered

Attack Indicators (4xx)

- 401 vs 403 difference → auth boundary mapping

- 403 turning into 200 → authorization bypass

- 404 on admin pages → forced browsing target

- 405 revealing allowed methods

Different 4xx codes often reveal internal access control logic.

5xx – Server Error Responses

5xx responses indicate server-side failures. These are highly valuable to attackers because they often reveal bugs, crashes, or misconfigurations.

- 500 Internal Server Error – Unhandled exception

- 502 Bad Gateway – Upstream failure

- 503 Service Unavailable – Overload or downtime

- 504 Gateway Timeout – Backend delay

Attack Indicators (5xx)

- 500 after input change → injection attempt

- Stack traces → information disclosure

- 502/504 → request smuggling clues

- 503 under load → DoS vector

Reproducible 5xx errors often lead to high-impact vulnerabilities.

Mapping Status Codes to Vulnerabilities

| Status Code | Possible Issue |

|---|---|

| 200 | IDOR, auth bypass |

| 302 | Logic flaw, open redirect |

| 401 | Authentication enforcement |

| 403 | Authorization boundary |

| 404 | Forced browsing target |

| 500 | Injection, crash, misconfig |

HTTP status codes are not just responses — they are signals that reveal how an application thinks.

3.7 HTTP Headers Abuse & Manipulation

HTTP headers are key–value pairs sent with every request and response. They provide extra information about the client, request, and data format. From a security perspective, headers are dangerous because they are fully controlled by the client.

If the browser can send it, an attacker can change it.

📨 Important HTTP Request Headers

- Host – Which website the request is for

- User-Agent – Browser or app identity

- Authorization – Login token or credentials

- Content-Type – How the request body should be parsed

- X-Forwarded-For – Original client IP (proxy header)

Developers often trust these headers for routing, access control, or security checks. That trust is frequently misplaced.

📄 Example HTTP Headers

Host: api.example.com

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0

Authorization: Bearer eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIs...

Content-Type: application/json

X-Forwarded-For: 127.0.0.1

🚨 Common Header Abuse (Easy Explanation)

1️⃣ IP Spoofing via Proxy Headers

Some applications trust headers like

X-Forwarded-For to identify the client IP.

Attackers can simply fake this header.

X-Forwarded-For: 127.0.0.1

2️⃣ Host Header Attacks

The Host header tells the server which domain is being accessed. If this header is trusted blindly, attackers can:

- Generate malicious password reset links

- Poison caches

- Bypass virtual host restrictions

Host: attacker.com

3️⃣ Authorization Header Abuse

The Authorization header carries login tokens. Common mistakes include:

- Not validating token ownership

- Accepting expired tokens

- Missing authorization checks

4️⃣ Content-Type Confusion

Content-Type tells the server how to parse the body. Changing it can confuse validation logic.

Content-Type: text/plain

- JSON validation bypass

- WAF bypass

- Parser inconsistencies

5️⃣ User-Agent Trust Issues

Some applications behave differently based on the User-Agent.

- Mobile-only features

- Admin panels for internal tools

- Debug modes

🧠 Why Header Abuse Works

- Headers look “system-generated”

- Developers assume browsers won’t modify them

- Security logic is placed in headers

- Proxies add complexity and confusion

🧪 Pentester Header Testing Checklist

- Modify one header at a time

- Observe response code changes

- Test trusted headers (Host, X-Forwarded-For)

- Change Content-Type with same body

- Replay requests with modified Authorization

Headers are powerful, invisible, and dangerous. Never assume headers are trustworthy.

3.8 Cookies, Sessions & Authentication Flow

HTTP is stateless. Sessions and cookies are used to maintain user identity.

🔐 Common Session Weaknesses

- Predictable session IDs

- Session fixation

- Missing expiration

- Insecure cookie flags

3.9 Web Server Logs & Forensic Evidence

📜 Why Logs Matter

- Detect attacks

- Investigate incidents

- Provide legal evidence

📌 Common Logged Data

- IP addresses

- Request paths

- Response codes

- Timestamps

3.10 TLS / SSL Basics & Secure Channel Concepts

SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) and its successor TLS (Transport Layer Security) are cryptographic protocols designed to create a secure communication channel between a client and a server over an untrusted network such as the Internet.

SSL is now deprecated. In modern systems, the term “SSL” commonly refers to TLS 1.2 and TLS 1.3, which are currently considered secure and industry-approved.

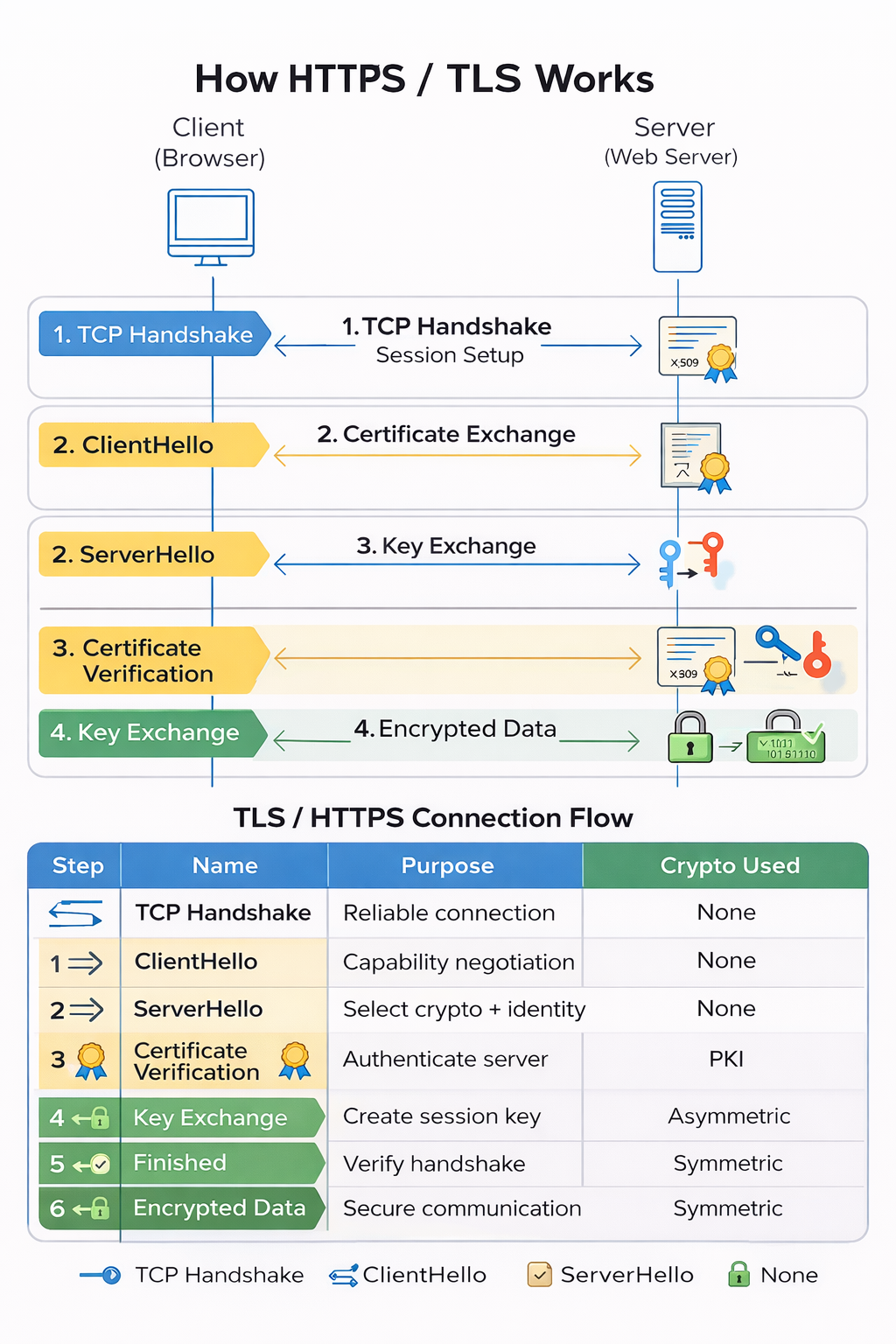

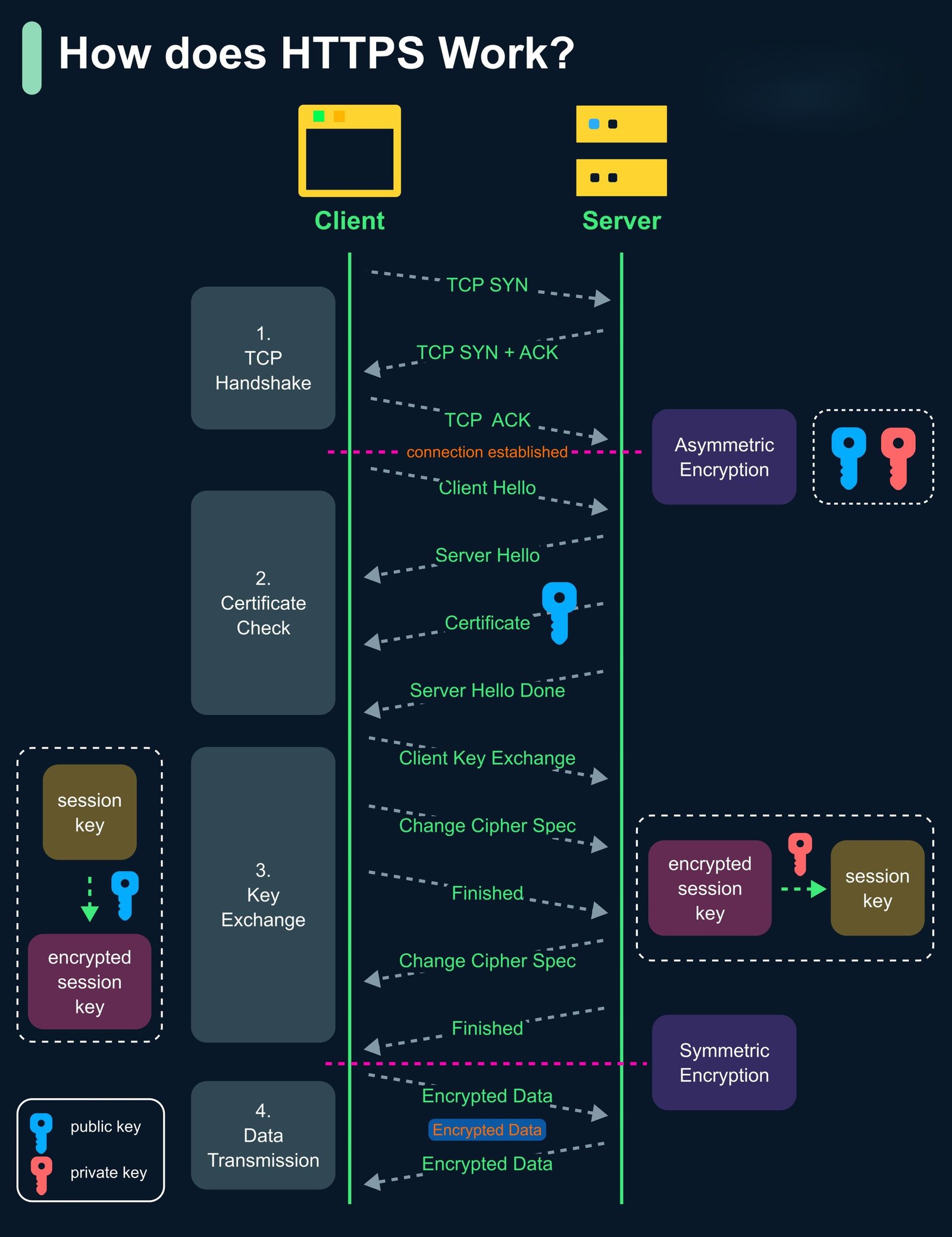

High-Level HTTPS & TLS Flow

Secure web communication follows a layered process: TCP connection → TLS handshake → encrypted application data.

TCP establishes reliability first, TLS adds encryption and trust, then application data flows securely.

Security Goals of TLS

- Confidentiality – Data is encrypted so attackers cannot read it.

- Integrity – Data cannot be altered without detection.

- Authentication – The client verifies the server’s identity.

Step 0: TCP Handshake (Before TLS)

TLS does not work without TCP. A reliable TCP connection must be established first using a 3-way handshake.

| Step | Direction | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| SYN | Client → Server | Request connection |

| SYN-ACK | Server → Client | Acknowledge request |

| ACK | Client → Server | Confirm connection |

TLS Handshake – Detailed Conceptual Flow

Asymmetric cryptography establishes trust; symmetric encryption protects data.

-

ClientHello

Client sends supported TLS versions, cipher suites, random value, and extensions (SNI, ALPN). -

ServerHello

Server selects TLS version, cipher suite, and sends its digital certificate. -

Certificate Verification

Client validates:- Trusted Certificate Authority (CA)

- Domain name (CN / SAN)

- Validity period

- Signature algorithm

-

Key Exchange

A shared session key is securely established using RSA (legacy) or ECDHE (modern). -

Secure Session Established

Symmetric encryption (AES / ChaCha20) is now used for all communication.

Old vs Modern TLS Flow

| Aspect | Old (SSL / TLS 1.0–1.1) | Modern (TLS 1.2 / 1.3) |

|---|---|---|

| Status | Deprecated ❌ | Secure & Approved ✅ |

| Key Exchange | Static / RSA | ECDHE (Forward Secrecy) |

| Ciphers | RC4, DES, SHA-1 | AES-GCM, ChaCha20 |

| Handshake Security | Partially exposed | Encrypted (TLS 1.3) |

| Performance | Slower | Faster & optimized |

Encrypted Application Data Phase

After the TLS handshake completes, all application data (HTTP requests, API calls, credentials, cookies) is transmitted in encrypted form.

HTTP GET /login ❌ (Plaintext)

HTTPS GET /login ✅ (Encrypted via TLS)

Ethical hackers verify TLS versions, cipher strength, certificate validity, and configuration — not exploit encryption.

03.11 TLS Abuse, Certificate Analysis & Evidence

While TLS provides strong security, misconfigurations, weak certificates, or improper implementations can still expose applications to serious risks. Ethical hackers must identify and document these weaknesses responsibly.

Common TLS Misconfigurations & Abuse

- Expired or self-signed certificates

- Weak or deprecated cipher suites

- Support for old TLS versions (TLS 1.0 / 1.1)

- Improper certificate validation

- Missing certificate chain (intermediate CA)

- Insecure renegotiation settings

Digital Certificate Analysis (Conceptual)

A digital certificate binds a public key to an identity. Ethical hackers must inspect certificates to ensure trust is properly established.

Key Certificate Fields to Review

- Common Name (CN) & Subject Alternative Names (SAN)

- Issuer (Certificate Authority)

- Validity period (Not Before / Not After)

- Public key algorithm and size

- Signature algorithm (SHA-256, SHA-1, etc.)

🔍 Indicators of Weak or Abusive TLS Usage

- Browser security warnings

- Certificate mismatch errors

- Untrusted CA alerts

- Mixed content warnings (HTTPS + HTTP)

- Absence of HSTS headers

Evidence Collection (Ethical & Defensive)

During assessments, TLS issues must be documented clearly and responsibly. Evidence should focus on configuration state, not exploitation.

Acceptable Evidence Examples

- Certificate details (issuer, expiry)

- Supported TLS versions

- Cipher suite configuration

- Browser or tool warnings

- Server response headers

TLS Hardening Best Practices

- Use TLS 1.2 or TLS 1.3 only

- Disable weak ciphers and protocols

- Use strong certificates (RSA 2048+ or ECC)

- Enable HSTS

- Regular certificate renewal and monitoring

TLS failures are usually configuration problems, not cryptographic weaknesses.

03.12 Web Servers Explained (Apache, Nginx, IIS)

A web server is the first major processing layer that interacts with client requests over HTTP and HTTPS. It is responsible for receiving, parsing, validating, routing, and responding to requests before they reach any application logic.

Because web servers operate at the protocol and transport boundary, implementation differences directly influence how requests are interpreted, logged, forwarded, or rejected — making them a critical component of the overall attack surface.

Core Responsibilities of a Web Server

- Accepting TCP connections and managing client sessions

- Negotiating TLS for encrypted communication

- Parsing HTTP requests (methods, headers, paths, parameters)

- Serving static content such as HTML, CSS, JavaScript, and images

- Forwarding dynamic requests to backend application servers

- Generating responses and enforcing protocol compliance

- Recording access and error logs for monitoring and forensics

Common Web Server Types

- Apache HTTP Server – Uses a process or thread-based model, supports per-directory configuration, and is widely deployed in shared hosting environments.

- Nginx – Uses an event-driven, asynchronous model, commonly deployed as a reverse proxy, load balancer, or edge server in modern architectures.

- Microsoft IIS – Integrated with the Windows ecosystem, tightly coupled with ASP.NET and Active Directory-based environments.

Authoritative vs Unauthoritative Servers

In modern web applications, a single user request often passes through multiple servers. However, not every server should be trusted to make important security decisions.

Authoritative Server (Easy Definition)

An authoritative server is the server that makes the final decision about what a user is allowed to do. It has complete knowledge of the user, their permissions, and the application’s rules.

- Decides whether a user is authenticated or not

- Checks user roles, permissions, and access rights

- Applies business logic and security rules

- Directly talks to databases or sensitive services

- Usually the application server or API backend

Unauthoritative Server (Easy Definition)

An unauthoritative server is a server that helps move the request but should not decide what the user is allowed to access.

- Routes or forwards requests to other servers

- Handles performance, caching, or load balancing

- Does not fully understand user identity or permissions

- Often relies on headers or metadata provided in the request

- Common examples include reverse proxies and web servers like Apache or Nginx

Trust Boundaries and Security Implications

- Headers added by a client may be trusted incorrectly by upstream servers

- IP-based access controls can fail when proxies are involved

- URL rewriting and normalization may differ between layers

- Frontend validation may not match backend enforcement

- Logging may occur on one layer while decisions happen on another

Security Relevance for Ethical Hackers

- Identifying which server is authoritative for security decisions

- Understanding how headers influence routing and access control

- Recognizing reverse proxy and load balancer behavior

- Detecting mismatches between frontend and backend validation

- Interpreting server responses and logs accurately

Web server vulnerabilities are often the result of trust and logic errors, not protocol flaws. Understanding server roles is essential for accurate assessment.

03.13 Application Servers vs Web Servers

Web servers and application servers serve fundamentally different purposes within a web architecture. Confusing these roles leads to incorrect security assumptions, misplaced trust, and exploitable attack paths.

Modern web applications commonly deploy both server types together, creating layered request processing where responsibility must be clearly defined and enforced.

Web Server Responsibilities

- Accepting client connections and managing HTTP sessions

- Parsing HTTP requests (methods, headers, URLs, parameters)

- Terminating TLS and enforcing transport-level security

- Serving static content efficiently

- Routing and forwarding requests to backend services

- Applying basic access restrictions and rate limits

Application Server Responsibilities

- Executing application and business logic

- Handling authentication workflows

- Performing authorization and role validation

- Interacting with databases and internal services

- Processing user input and enforcing data integrity

- Generating dynamic responses

Typical Deployment Architecture

- Client → Web Server (reverse proxy)

- Web Server → Application Server

- Application Server → Database or internal APIs

Trust Boundary Breakdown

- Frontend validates input, backend assumes it is safe

- Headers added or modified during request forwarding

- IP-based access control evaluated at the wrong layer

- Inconsistent URL normalization and decoding

- Authentication state inferred instead of verified

Security Implications

- Authentication bypass due to mismatched validation

- Authorization flaws caused by trust assumptions

- Request smuggling between frontend and backend

- Exposure of internal APIs or admin functionality

- Incomplete or misleading security logs

Defensive Design Principles

- Enforce authentication and authorization at the application server

- Minimize trust in forwarded headers and client-supplied data

- Ensure consistent request normalization across layers

- Log security-relevant events at authoritative components

- Clearly document responsibility boundaries between servers

Many critical vulnerabilities arise not from bugs in code, but from incorrect assumptions about which server is responsible for enforcing security.

03.14 Server Request Handling & Attack Surface

Every HTTP request passes through multiple processing stages across web servers, proxies, and application servers. Each stage performs interpretation, transformation, or validation, introducing potential gaps between what the client sends and what the server understands.

These gaps define the server-side attack surface, where inconsistent parsing, misplaced trust, or incomplete validation can lead to security failures.

Request Lifecycle Overview

- Connection establishment – TCP connection setup and session handling

- TLS negotiation – Encryption, certificate validation, and cipher agreement

- Initial request parsing – Method, headers, path, and protocol interpretation

- Normalization & decoding – URL decoding, canonicalization, and rewriting

- Routing decisions – Mapping requests to handlers or backend services

- Application logic execution – Authentication, authorization, and business rules

- Response generation – Status codes, headers, and body creation

- Logging & monitoring – Recording activity for auditing and detection

Key Request Handling Components

- HTTP method handling – Determines permitted actions and side effects

- Header processing – Influences routing, authentication, and caching

- Path resolution – Controls file access and endpoint selection

- Parameter parsing – Shapes application behavior and logic flow

- State management – Session, cookie, and token handling

Major Attack Surfaces

- Inconsistent handling of HTTP methods across layers

- Blind trust in forwarded or client-controlled headers

- Differences in URL decoding and normalization rules

- Frontend validation not enforced by backend logic

- Security decisions made by unauthoritative components

- Logging that does not reflect actual request behavior

Frontend vs Backend Interpretation

- Web servers may rewrite URLs before forwarding

- Proxies may add, remove, or modify headers

- Application servers may re-parse requests independently

- Security controls may exist at only one layer

Logging, Visibility & Evidence

- Different layers may log different representations of a request

- Frontend logs may not reflect backend processing

- Backend errors may be masked by proxies

- Insufficient logging limits detection and forensic analysis

Defensive Perspective

- Centralize authentication and authorization logic

- Apply consistent request normalization across layers

- Avoid trusting client-controlled or forwarded headers

- Ensure security checks are enforced at authoritative servers

- Correlate logs across frontend and backend components

Most server-side vulnerabilities originate from logic gaps and trust assumptions, not weaknesses in the HTTP protocol itself.

Module 03-A : Code Injection

This module provides an in-depth understanding of Code Injection vulnerabilities, where untrusted user input is executed as application logic. Code Injection is one of the most dangerous classes of vulnerabilities because it can lead to full application compromise, data theft, and remote code execution. This module builds directly on Module 03 (HTTP & Transport Abuse) by explaining how malicious HTTP input becomes executable code inside applications.

3A.1 Understanding Code Injection Flaws

🔍 What is Code Injection?

Code Injection occurs when an application dynamically executes code constructed using untrusted input. Instead of being treated as data, user input is interpreted as program instructions.

User-controlled input becomes executable logic inside the application runtime.

🧠 Why Code Injection Is Critical

- Leads to remote code execution (RCE)

- Allows attackers to bypass all business logic

- Often results in complete server compromise

- Hard to detect with traditional security controls

📌 Common Root Causes

- Dynamic code evaluation (eval-like functions)

- Unsafe deserialization

- Template engines with logic execution

- Improper input validation

- Mixing code and data

3A.2 Code Injection vs OS Command Injection

⚖️ Key Differences

| Aspect | Code Injection | OS Command Injection |

|---|---|---|

| Execution Context | Application runtime (language interpreter) | Operating system shell |

| Typical Impact | Logic manipulation, RCE | System-level command execution |

| Detection Difficulty | Very high | High |

| Common Functions | eval(), exec(), Function() | system(), exec(), popen() |

3A.3 Languages Commonly Affected

🧩 PHP

- eval()

- assert()

- preg_replace with /e modifier

- Dynamic includes

🐍 Python

- eval()

- exec()

- pickle deserialization

- Dynamic imports

🟨 JavaScript

- eval()

- Function()

- setTimeout(string)

- setInterval(string)

3A.4 Exploitation Scenarios & Impact

🎯 Common Exploitation Paths

- Template injection leading to logic execution

- Unsafe configuration parsers

- Dynamic expression evaluators

- Deserialization of untrusted data

💥 Impact Analysis

- Complete application takeover

- Credential theft

- Database manipulation

- Lateral movement inside infrastructure

Unexpected crashes, unusual logic execution, or unexplained privilege escalation often indicate code injection.

3A.5 Secure Coding Defenses & Prevention

🛡️ Core Defense Principles

- Never execute user-controlled input

- Eliminate dynamic code evaluation

- Strict separation of code and data

- Use allow-lists, not deny-lists

✅ Secure Design Practices

- Use parameterized logic instead of dynamic expressions

- Adopt safe template engines

- Disable dangerous language features

- Perform security-focused code reviews

- No eval / exec usage

- No dynamic function construction

- Strict input validation

- Runtime security monitoring

Code Injection is a high-impact vulnerability that turns user input into executable logic. Preventing it requires secure design decisions, not just filtering or patching.

Module 04 : Unrestricted File Upload

This module provides an in-depth analysis of Unrestricted File Upload vulnerabilities, one of the most commonly exploited and high-impact web application flaws. Improper file upload handling can allow attackers to upload malicious scripts, web shells, configuration files, or executables, often resulting in remote code execution, data compromise, or full server takeover.

4.1 Dangerous File Upload Risks

📂 What Is an Unrestricted File Upload?

An Unrestricted File Upload vulnerability occurs when an application allows users to upload files without sufficient validation of file type, content, size, name, or storage location.

Attacker-controlled files are stored and processed by the server.

🧠 Why File Uploads Are High-Risk

- Files can contain executable code

- Files may be directly accessible via the web

- Upload features often bypass authentication checks